Change Data Capture (part 1)

At Materialize we traffic in computation over data that change. As a consequence, it is important to have a way to write down and read back changes to data. An unambiguous, robust, and performant way to write down and read back changes to data.

What makes this challenging? Why not just write out a log of whatever happens to the data?

If you are familiar with the modern stream storage system---Kafka, Kinesis, Pulsar, Azure Event Hubs---you may know how awkwardly our three desiderata interact. If you want performance, you should expect to read concurrently from streams that are not totally ordered. If you want robustness you'll need to be prepared for duplication in your streams as at-least-once stream storage systems cope with anomalies. Life can be pretty hard if you want correct answers in a distributed setting.

This post will talk through a change data capture protocol: how one writes down and reads back changes to data. This protocol allows arbitrary duplication and reordering of its messages, among other anomalies, while maintaining a compact footprint in memory. These features allow us to use streaming infrastructure that does not protect against these issues (most of them), but they also allow us to introduce several new benefits which we will get to by the post's end.

It's probably worth stressing that this isn't something Materialize is landing tomorrow. The post is more of an exploration of how we can capture and replay the data that Differential Dataflow produces. The code will be landing in the Differential Dataflow repository, and should be broadly useful. This is also only part 1; we'll talk through the protocol and a single-threaded implementation of the reader, but we won't get as far as the data-parallel implementation in differential dataflow (which does seem to work!).

Data that Change

Let's start out by looking at the problem we have to deal with.

Materialize maintains computations over data that change. The data are large relational collections whose individual records may come and go for reasons we can neither anticipate or constrain. All we know is that as time progresses, the data change.

We can record the changes that happen to the data by writing down the records that are added to and removed from the collection at each time. Materialize is based on differential dataflow which does this with "update triples" of 1. the record that changed, 2. the time it changed, and 3. how it changed (was it added or removed).

Let's take an example:

1 | |

2 | |

3 | |

4 | |

5 | |

6 | |

7 | |

8 | |

9 | |

10 | |

11 | |

12 | |

13 | |

We see a sequence of changes, ordered by the three times time0, time1, and time2. At time0 we see four records are introduced. It turns out one record was added twice but collections are multisets so that can happen. At time1 we see both a deletion and an addition of a record. We can interpret this (perhaps incorrectly) as an update to record1 that changes it to record4; again we aren't worried about the reason for the change, just what the change was. Finally, at time2 we see the deletion of two records.

This is the sort of information we want to record. An evolving history of what happens to our data, as time advances.

In fact we want to know just a bit more. In the transcript up above we see changes through time2, but we don't actually know that we won't see another update at time2. Alternately, perhaps the history is correct even through some time3 > time2. How do we communicate that the absence of information is information itself, without accidentally implying that there are no more changes coming at all?

Our history has updates to data, but we can also provide progress statements that advance the clock of times that are still due to come. These statements have a few names depending on your background: watermarks, punctuation, frontiers. We'll just use a simple statement finish time to mean that all of the updates for time and any earlier times have now been presented.

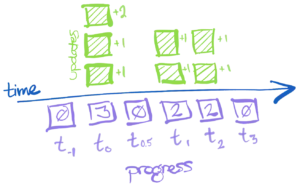

Here is a history with progress statements.

1 | |

2 | |

3 | |

4 | |

5 | |

6 | |

7 | |

8 | |

9 | |

10 | |

11 | |

12 | |

13 | |

I put in a finish time2 statement to show that we can close out the time2 updates, but also a finish time3 statement to show that we might want to communicate that times are closed even when there are no updates.

Anomalies and Opportunities

Because computer systems are complicated, we can't simply write down the history above and expect everything to work out. Because computer systems are complicated, they will occasionally reorder or duplicate records. Mostly, this is because people want to use more than one computer, and as soon as you start doing that any two computers rarely agree on how things were supposed to happen.

Anyhow, modern stream storage like Kafka, Kinesis, Pulsar, and Azure Event Hubs have quirks that mean if you want both performance and fault-tolerance, your data might get shuffled around and duplicated. On the plus side, you are pretty sure that what you write will be recorded and eventually available to readers. This is way better than the alternative of losing data; having too much information beats having not enough information.

It probably wouldn't take much to convince you that the history as written above loses something when you reorder and duplicate rows in it. If you repeat an update statement, you might believe that you should do the update twice (we actually do have a repeat in our history, but it is intended!). If you reorder a finish statement, you may prematurely conclude that the data have ceased changing and then miss some updates. The format as presented above is pretty easy for us humans to read, but it isn't great when uncooperative computers get their hands on it and change how it is laid out.

We'll want a way to present the information that protects us against these vagaries of uncooperative computers, specifically duplication and reordering.

At the same time, if we immunize ourselves to duplication and reordering we are provided with some new opportunities!

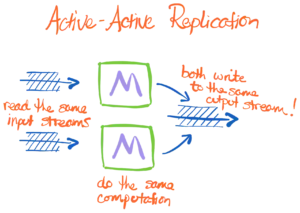

- If our representation can be written and read in any order, then we can deploy a large number of concurrent writers and readers. We may be able to grind through a history much more quickly as a result. The number of readers and writers can be scaled up and down, and doesn't need to be baked in to the representation.

- If our representation can tolerate arbitrary duplication, then we can use multiple computers to reduntantly compute and write out the results. This provides so-called active-active fault-tolerance, which duplicates work but insures against the failure (or planned outage) of individual workers.

There are several other advantages to these degrees of robustness, from resharding streams of data to easing the reintroduction of new or recovered replicas. Migrating between query plans without interruption. Stuff like that. I just made those up, but lots of operational simplicity emerges.

Materialize CDCv2

Let's get right in to the proposal.

A Sketch

We will make two types of statements, each of which will be statements that are both true about the final history and can be made before that history is complete. We will make these statements only once we are certain they are and will remain true.

- Update statements have the form

update (data, time, diff)and indicate that the change thatdataundergoes attimeis exactlydiff. This means there should be only one entry for each(data, time): whatever the accumulateddiffvalues end up being. We don't write down updates that have a zero value fordiff. - Progress statements have the form

progress (time, count)and report the number of distinct non-zero updates that occur attime.

For the example from up above, we might write

1 | |

2 | |

3 | |

4 | |

5 | |

6 | |

7 | |

8 | |

9 | |

10 | |

11 | |

12 | |

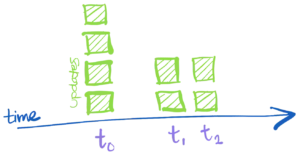

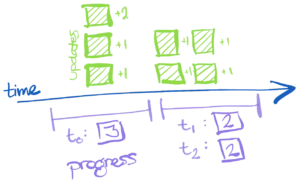

There could actually be other times too, and if so we should write them down with their zero counts. In picture form, it might look something like this:

Clearly I've had to make up some new times to fit around time0 and time1, but I hope you'll excuse that!

The statements above may be arbitrarily duplicated and reordered, and we can still recover as much of the history as is fully covered by the update and progress statements.

We will work through the details of the recovery process, but ideally the intuition is clear about why this might work. As we collect statements, we can start to re-assemble the puzzle pieces of the history of the collection. We can place updates at moments in time, and we learn how many updates it takes for the set at a time to be complete. We can perform this work even if statements come out of order, and any duplicate information should just corroborate what we already know.

In addition to putting the puzzle back together, we get the appealing (and often overlooked) property that we do not need to maintain unboundedly long histories to do so. As moments in time become finished we can flip a bit for the time to indicate that it is full and discard all of the updates we have, as well as future updates for the time. As intervals in time become finished we can retain only their upper and lower bounds.

An Implementation

First off, we are going to change the structure of statements to run a bit more lean. Update statements will contain batches of updates, and progress statements will be about intervals of times. The specific Rust types that I am using are

1 | |

2 | |

3 | |

4 | |

5 | |

6 | |

7 | |

8 | |

9 | |

10 | |

11 | |

12 | |

Clearly we've just deferred the complexity of the progress messages. Here it is.

1 | |

2 | |

3 | |

4 | |

5 | |

6 | |

7 | |

8 | |

9 | |

10 | |

11 | |

12 | |

13 | |

14 | |

15 | |

The lower and upper bounds are each vectors of time, which might seem odd at first. In our world, times aren't necessarily totally ordered, and an interval of time is better explained by two sets of times, where the interval contains those times that are greater than or equal to an element of lower and greater than or equal to no elements of upper. You are welcome to think of them as integers, but bear in mind that upper could also be empty (which is how one indicates an interval that ends a stream).

Here is a picture that hints at what is different with the progress statements:

Notice that rather than one progress message for each time, we have intervals of times in which we record only those counts with non-zero times.

You may have noticed that we've introduced some non-determinism into our protocol: how we batch updates and progress statements. It's worth clearly stating that we will be able to tolerate not only literal duplication and reordering of messages, but also duplication and reordering of the information in the messages, even with different batching of that information.

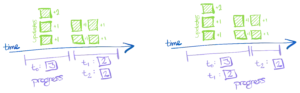

For example, the following figure presents two ways we could have batched progress information.

Even though there is not literal duplication between the two sets of progress statements, we'll end up recovering the puzzle just fine if someone mixed up the statements from the right and left side (or any other way that does not present conflicting information).

An Iterator

Although we'll eventually work through how one might implement this in a timely dataflow system (but not today), let's start with the simpler task of reordering and deduplicating an arbitrarily mangled input stream of Message records.

The iterater that I've written wraps around an arbitrary I: Iterator<Item = Message> which is Rust's way of saying "any specific type that can produce a sequence of Message items". It also wraps a bit of additional state as well, used to keep track of what we've seen. I've left the comments in, but if everything looks intimidating there are just six fields.

1 | |

2 | |

3 | |

4 | |

5 | |

6 | |

7 | |

8 | |

9 | |

10 | |

11 | |

12 | |

13 | |

14 | |

15 | |

16 | |

17 | |

18 | |

19 | |

20 | |

21 | |

22 | |

23 | |

24 | |

25 | |

26 | |

27 | |

28 | |

29 | |

30 | |

31 | |

32 | |

33 | |

34 | |

35 | |

36 | |

37 | |

38 | |

39 | |

40 | |

41 | |

42 | |

43 | |

44 | |

45 | |

46 | |

47 | |

48 | |

49 | |

50 | |

I thought for demonstration purposes I would have the iterator produce the update and finish statements we had back in the simple history. For reasons, I'd rather produce a batch of updates and one finish statement, all at the same time (it is easier to do that once for each call, than to trickle out updates one by one; you need another state machine to do that).

1 | |

2 | |

3 | |

4 | |

5 | |

6 | |

7 | |

8 | |

9 | |

10 | |

11 | |

12 | |

13 | |

14 | |

This is the structure of what we'll need to write: each time someone asks, we repeatedly interrogate the wrapped iterator until we realize that we've learned enough to produce a new announcement about updates that are now finished. It should then be a simple transformation to make it "push" instead of "pull", reacting to new messages sent to it.

We'll sketch out the body of the next method, leaving a few bits of logic undeveloped for the moment. The main thing we'll do in this cut is to process each received message, either Updates or Progress, and then call out what we'll need to do to afterwards. In fact, we can do the message receipt a few times if we want; we don't have to take a break for the clean up logic for each message.

1 | |

2 | |

3 | |

4 | |

5 | |

6 | |

7 | |

8 | |

9 | |

10 | |

11 | |

12 | |

13 | |

14 | |

15 | |

16 | |

17 | |

18 | |

19 | |

20 | |

21 | |

22 | |

23 | |

24 | |

25 | |

26 | |

27 | |

28 | |

29 | |

30 | |

31 | |

The only real work happens when we receive Updates, where we discard any updates that are 1. for times that we have already resolved, or 2. are already present in our deduplication stash. Surviving updates result in a decrement for the expected count at that time (even if the expected count is not yet postive; that message might come later), and get stashed to help with future deduplication.

The two remaining bits of logic are 1. how to integrate progress statements, which require some care because there may be gaps in our timeline, and 2. how to close out intervals of time when appropriate, which also requires some care.

We'll start with integrating progress statements.

1 | |

2 | |

3 | |

4 | |

5 | |

6 | |

7 | |

8 | |

9 | |

10 | |

11 | |

12 | |

13 | |

14 | |

15 | |

16 | |

17 | |

18 | |

Although this may look a bit beastly, I think it is mostly the while condition that is intimidating.

The while loop iterates as long as we can find a progress statement for whom self.progress_frontier is beyond the statement's lower bound; this ensures that we can cleanly graft the progress statement on to what we currently have. We then extract that statement, discard any counts for times that have already been resolved (are not beyond self.progress_frontier), incorporate any remaining statements as expected counts, and then extend self.progress_frontier to cover the upper bound of the progress statement.

And then we repeat, until we can't find a progress statement that can be cleanly grafted.

The last bit of logic is to look at what evidence we have accumulated, both self.progress_frontier and self.messages_frontier, and ensure that we report everything up through their lower bound.

1 | |

2 | |

3 | |

4 | |

5 | |

6 | |

7 | |

8 | |

9 | |

10 | |

11 | |

12 | |

13 | |

14 | |

15 | |

16 | |

17 | |

18 | |

That's it!

I'm sure it's been a bit of an exercise, but I hope the hand-drawn pictures have re-assured you that such a thing is possible.

Conclusions

We've seen how you can set up a protocol that records the timestamped changes collections undergo, in a way that is robust to duplication and reordering (and re-batching, for what that's worth). Just how exciting this is remains to be seen, but my sense is that this introduces substantial operational simplicity to settings where systems fail, systems lag, and generally folks may need to repeat work to be sure that it has been done. If multiple systems need to stay live as part of a live migration from one to another, or if the data itself needs to be migrated from relatively faster and pricier storage off to somewhere colder, this protocol seems helpful.

There are surely other protocols that provide qualitatively similar properties; I'm not trying to claim that we've invented anything here. But, part of the exercise is making sure you understand a thing, and I've certainly been helped by that. I hope you have as well!