Efficient Real-Time App with TAIL | Materialize

Within the web development community, there has been a clear shift towards frameworks that implement incremental view maintenance and for good reason. When state is updated incrementally, applications perform better and require fewer resources. Using Materialize, developers and data analysts can adopt the same, event driven techniques in their data processing pipelines, leveraging existing SQL know-how. In this blog post, we will build an application to demonstrate how developers can create real-time, event-driven experiences for their users, powered by Materialize.

This post is the fulfillment of the goals that I had when writing Streaming TAIL to the Browser. That post is not required to understand this post but familiarizing yourself with the TAIL command is recommended.

Overview

Demonstration of What We Will Be Building

In this post, we are going to use the demo from our documentation's Get Started tutorial as the basis for building a minimal web application. The application allows users to see the total number of edits made to Wikipedia, as well as a bar chart of the top 10 editors. Here is an animation that shows the final result:

Want to run this demo yourself? Awesome! Clone our repository and follow the instructions for Running it Yourself.

Desired Properties of the Solution

Before jumping into how to build this, let's outline the desired properties for our solution. The final solution should be:

- Push-Based - Instead of having the client poll for updates, updates should be initiated by the server and only when the client state is outdated.

- Complete - Clients should present both a consistent and complete view of the data, regardless of when the application is loaded.

- Unbuffered - Clients should receive updates as soon as changes are made to the underlying datasets, without arbitrary delays in the data pipeline.

- Economic - Size of updates should be a function of the difference between the current state and the desired state. Additionally, clients should not be required to replay state from the start of history.

- Separation of Concerns - Applications modifying the source data (writers) should not need to know anything about the applications consuming the data (readers).

While it is possible for other applications to meet several of these properties, I hope that this application will demonstrate why the solution presented is ideal for this scenario. A discussion of why this application meets the above properties, and why other solutions likely do not, is presented further down in this post.

Overall Architecture

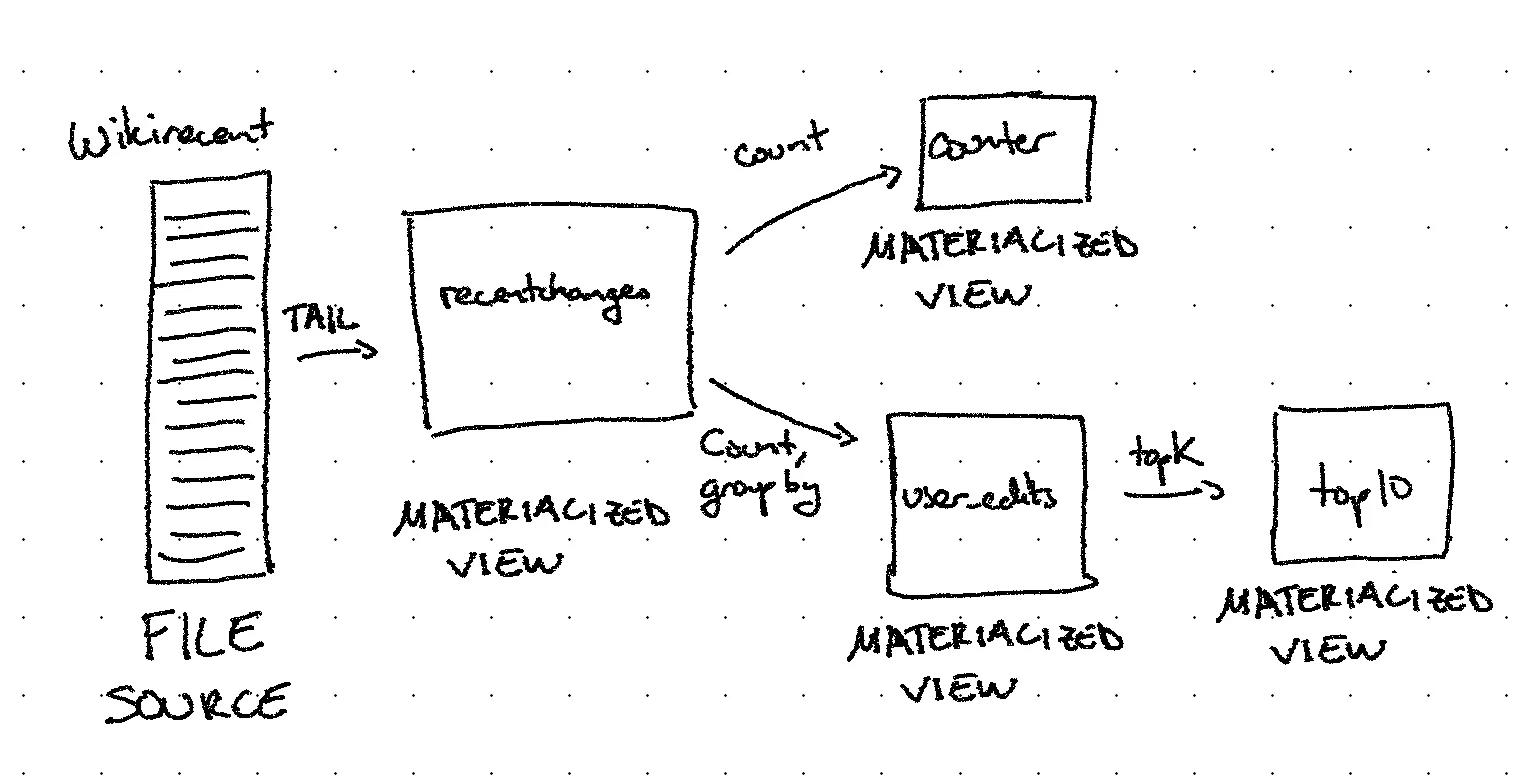

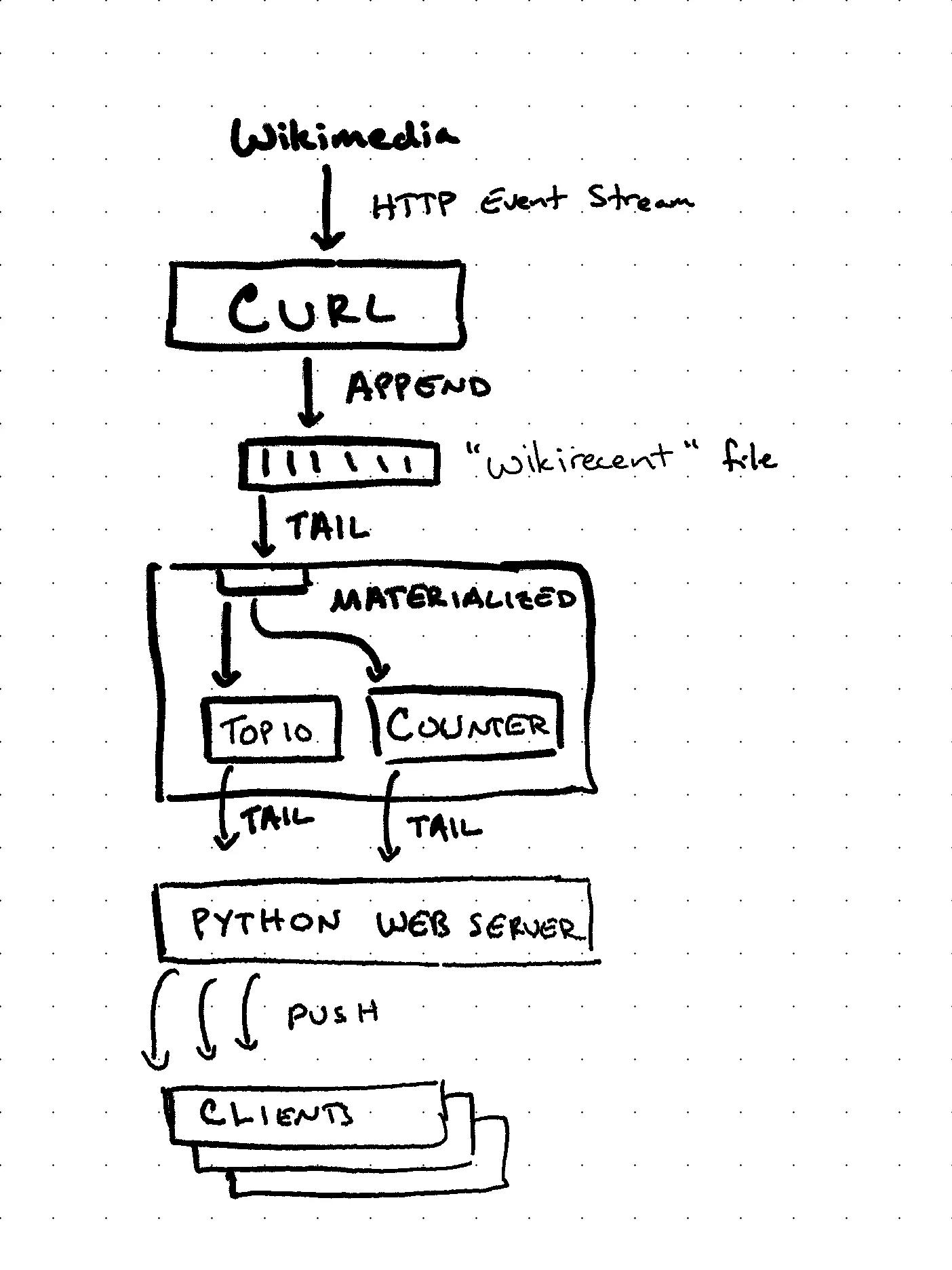

For those unfamiliar with our getting started demo, here is the flow of data in our pipeline:

Looking at the system diagram below, we see that the entire data pipeline is contained within a single materialized instance:

Let's discuss the role of each service in the diagram above.

If you started the application, you can run mzcompose ps to see the containers started.

curl -- wikirecent_stream_1

This container runs curl to stream Wikimedia's recent changelog to a file called recentchanges within a Docker volume shared with our materialized instance.

materialized -- wikirecent_materialized_1

This container runs an instance of materialized, configured to tail the recentchanges file and maintain our two materialized views: counter and top10. The views in this instance are configured exactly as documented in Getting Started - Create a real-time Stream.

Python web server -- wikirecent_app_1

This container runs a Python web server that hosts the code for our JavaScript application and converts the row-oriented results from TAIL to the batch-oriented results expected by our application.

Building Our Application

Our example application is an asynchronous Python web server built using two libraries: Tornado and psycopg3. There are three components to our application that I would like to call out:

- Python code to subscribe to materialized view updates using the

TAILcommand and convert the row-oriented results into batches. - Python code to broadcast batches to listeners.

- JavaScript code to apply batch updates for efficient browser updates.

Note: Materialize uses the word batch to refer to a data structure that expresses the difference between prior state and desired state. You can think of a batch as a "data diff".

Output for Our JavaScript Code

To efficiently update our client view state, we wish to present a stream of batches over a websocket to any configured listeners. We define a batch as the following:

1 | |

2 | |

3 | |

4 | |

5 | |

6 | |

7 | |

8 | |

9 | |

When a client first connects, we send a compacted view of all batches from the beginning of history:

1 | |

2 | |

3 | |

4 | |

5 | |

6 | |

7 | |

8 | |

9 | |

10 | |

11 | |

How can listeners bootstrap their state using a batch object? If there is one property that I find particularly beautiful about this solution, it's that first batch applied to an empty list is our initial state. This means that initializing and updating are the same operation. This batch object is so useful that D3's update and Vega's change APIs expect updates to come in a similar form.

However, results from tail are row-oriented. We need a little bit of code to convert from rows to batches; here is an example of the desired conversion:

1 | |

2 | |

3 | |

4 | |

5 | |

6 | |

7 | |

8 | |

9 | |

10 | |

11 | |

Let's look at the code to subscribe to view updates and transform rows into batches.

Subscribing to TAIL

To process rows from TAIL, we must first declare a cursor object that will be used to indefinitely iterate over rows. To help with our code know when to broadcast an update, we ask for progress markers in the response:

1 | |

2 | |

3 | |

4 | |

5 | |

6 | |

7 | |

Converting Rows to Batches

We've now created a communication channel which can be used to await results from the tail query. Whenever our view changes, our application will be notified immediately and we can read the rows from our cursor object. tail_view_inner implements the logic to process rows and convert them to batches:

1 | |

2 | |

3 | |

4 | |

5 | |

6 | |

7 | |

8 | |

9 | |

10 | |

11 | |

12 | |

13 | |

14 | |

15 | |

16 | |

17 | |

18 | |

19 | |

20 | |

21 | |

22 | |

23 | |

Updating Internal State and Broadcasting to Listeners

Now that we have a batch object, we apply this change to our own internal VIEW and broadcast the change to all listeners:

1 | |

2 | |

3 | |

4 | |

5 | |

6 | |

7 | |

8 | |

9 | |

10 | |

11 | |

12 | |

13 | |

14 | |

15 | |

Design Decision: Experienced readers will note that by maintaining an internal copy of the view in our Python web server, we can reduce the number of connections to the materialize instance. This is a strictly optional design decision that I made when writing this code -- materialized connections are very light-weight when compared to other databases. We expect that there will be use cases where you will want one or more materialized connection per user. Consider temporary materialized views feeding dashboards personalized to each user, for example.

In the case of this application, I opted to reduce the connections out of habit rather than necessity. It does also enable a larger degree of fan-out, if we wanted to serve millions of clients, for example.

Updating User Views

Now that we have looked at the code for broadcasting an update, let's show how our JavaScript code consumes these batches. Our application is showing two things: a total edits counter and a top 10 chart:

Updating Total Edits Count

The Total Edits Counter only cares about the latest value from the counter view, which itself consists of only a single row. This means that we can implement a WebSocket listener for total counts that simply reads the first row from inserted and uses that to update our counter HTML element:

1 | |

2 | |

3 | |

4 | |

5 | |

6 | |

7 | |

8 | |

9 | |

Updating Our Top 10 Chart

The Top 10 Chart uses Vega-Lite to render a bar chart. Because our batch data structure maps directly to the vega.change method, we can follow their Streaming Data in Vegalite example. We do need to write a small amount of code to enable property lookups:

1 | |

2 | |

3 | |

4 | |

5 | |

6 | |

7 | |

8 | |

9 | |

10 | |

11 | |

12 | |

13 | |

14 | |

15 | |

16 | |

17 | |

18 | |

19 | |

20 | |

21 | |

22 | |

23 | |

24 | |

And that's it! When a new batch is received, Vega / Vega-Lite updates just the elements that have changed and redraws our chart. We now have a real-time chart powered by a materialized view.

Wrapping Up Our Application

In this section, we saw how to build a truly end-to-end, event-driven pipeline that minimizes the amount of work required to build a real-time user experience. The code for synchronizing client state is simple and straightforward. There are no unnecessary delays introduced by polling and the updates are efficient to send and process. Now, let's revisit our desired properties to see how we did and to compare against other potential solutions.

Revisiting Our Desired Properties

From the example code above, we can see that our application meets the desired properties:

- Push-Based - Our Python server and Javascript applications receive batches as soon as they are available, sent over existing connections. Because materialized only produces batches when a view has changed, updates are only triggered when the client's state must change.

- Complete - The Python server always presents a complete view of the data, no matter when it starts up. Likewise, our Javascript clients always have a complete view of the data, no matter when they connect.

- Unbuffered - Materialize calculates batch updates as soon as the event data is written to the source file.

- Economic - Batch sizes are proportional to the difference between the prior state and new state. This reduces both the amount of data being sent over the network and the amount of work required to process each update. When clients first connect, they are not required to replay state from all of history; instead, clients receive an already compacted view of the current state.

- Separation of Concerns - The application writing data, curl, knows nothing about materialized views nor our JavaScript applications. It doesn't matter if we add additional views, join the

wikirecentstream with another data source or even change the existing queries -- we never need to modify our writer.

Things We Avoided

People have been building real-time applications for a long-time and Materialize makes it simple to build these applications without traditional limitations. Common drawbacks in other solutions include:

Repeated Polling / Continuous Query

Without incremental view updates, applications must constantly query the database for the results of a query. This results in increased load and network traffic on the database, as the full results of the query must be computed everytime. It also results in increased load on the web servers, as they must process the full result set on every query response.

Microservice Sprawl

Without incrementally maintained views defined in SQL, each materialized view would have required writing a custom stream processing function, as well as the creation of intermediate sources and sinks. Adding microservices would result in increased operational overhead and complexity of deployments.

Delays or Stalls in our Data Processing Pipeline

When batch updates are buffered, such as in ELT/ETL pipelines, applications are operating on old state. While it's tempting to think that it's just 5 minutes for a single view, the cumulative latency in the pipeline can be much worse. Delays in processing result in applications presenting incomplete and/or inconsistent state, especially when joining data across multiple sources. This reduces customer trust in your data pipeline.

Complicated Synchronization / Resynchronization Logic

Without incremental view updates, applications must implement their own logic to compute batches by comparing client and server state. This results in duplication of logic where you have one implementation for the initial update and another implementation for the incremental update. It also introduces edge cases when clients reconnect after a connection is dropped or closed. Implementing state synchronization logic in the application introduces additional complexity.

Duplicated Logic to Remove "Old" Data

Without the server telling the client what data is obsolete, long-lived clients are forced to implement their own logic to remove old data. While this might work for append-only datasets, most datasets have both inserts and deletes. Even if the sources are append-only, the downstream views may not be append-only, such as a top K query. Forcing the client to duplicate the server's logic to remove data leads to extra complexity during implementation and makes it harder to roll-out updates to the data pipeline.

Reader-Aware Writers

When the database cannot produce incremental updates, writers may notify listeners directly that the underlying data has changed. This is often done using side channels, such as LISTEN/NOTIFY, but this comes with its own set of drawbacks. Either the writer implements the logic required to produce an incremental update or the reader must fetch the entire dataset on each notification. Additionally, in the presence of dataflows, even simple ones such as our example application, determining who to notify is a non-trivial task.

Late-Arriving / Out-of-Order Data

Without joins that work over all data ingested, most stream processing systems will expire data based on the size of the window or the age of the data. In other frameworks, once the data is expired, you can no longer join against it. Temporal joins make it difficult to trust the results from your data pipeline.

Conclusion

Materialized makes writing real-time, event-driven applications simple and straightforward. This blog post presents an example application that demonstrates how to build real-time, data-driven application using the TAIL statement. Our application maintains several desirable properties in a real-time application while avoiding the common limitations present in other methods. Check out Materialize today!

Disagree with something I said? Have another method for performing the same task? I'd love to hear from you, either in our community or directly!

Love building applications like this? We're hiring!